Today, 7 teenagers will be told they have cancer. Despite being an issue that touches everyone (directly or indirectly), “the big C” is still a taboo topic because of the fear surrounding it. Research shows that as a result of cancer treatment in young people, 87% of patients lost contact with their friends. If we could just open up the dialogue around it, it’ll help aid those affected and could lead to risk elimination and early diagnosis.

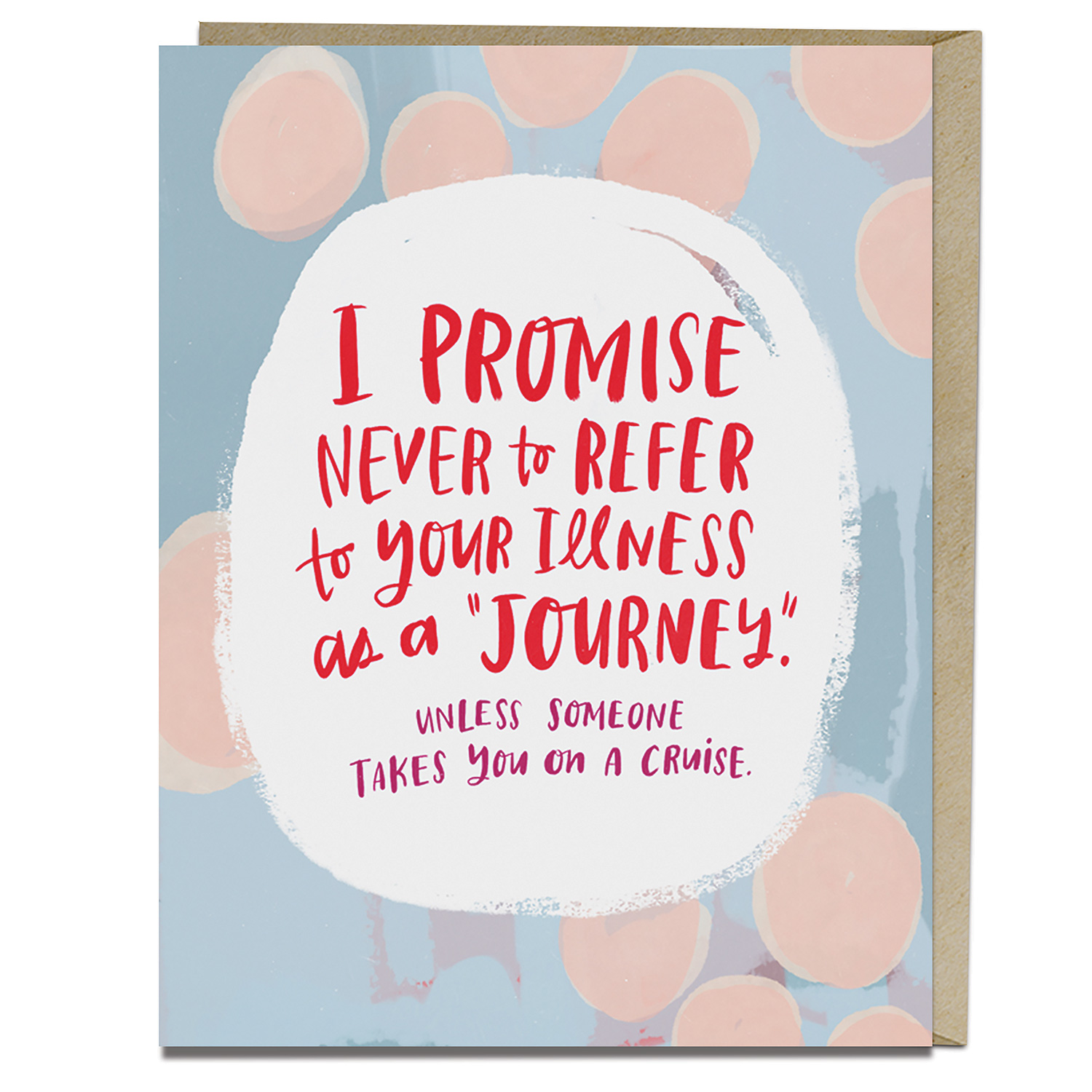

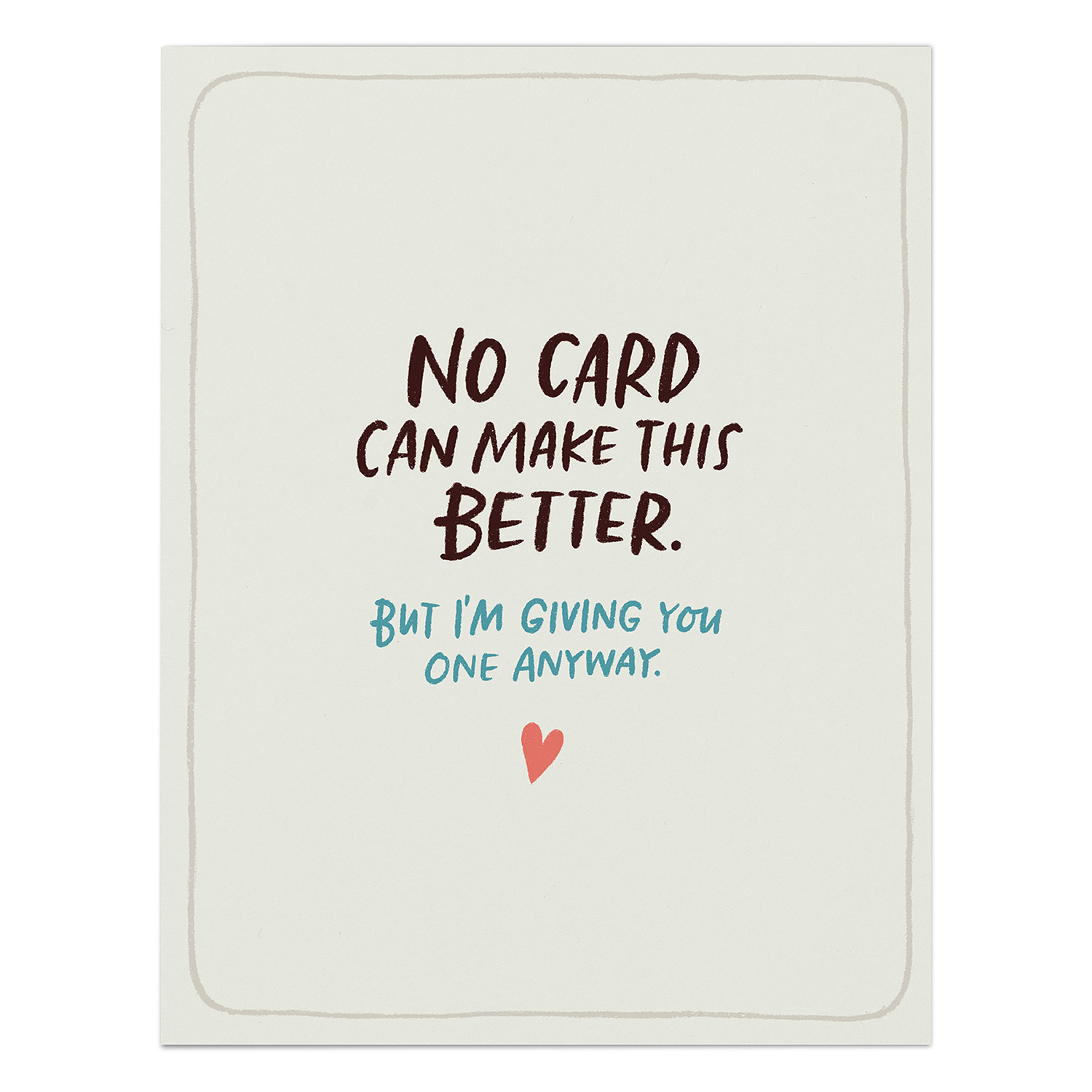

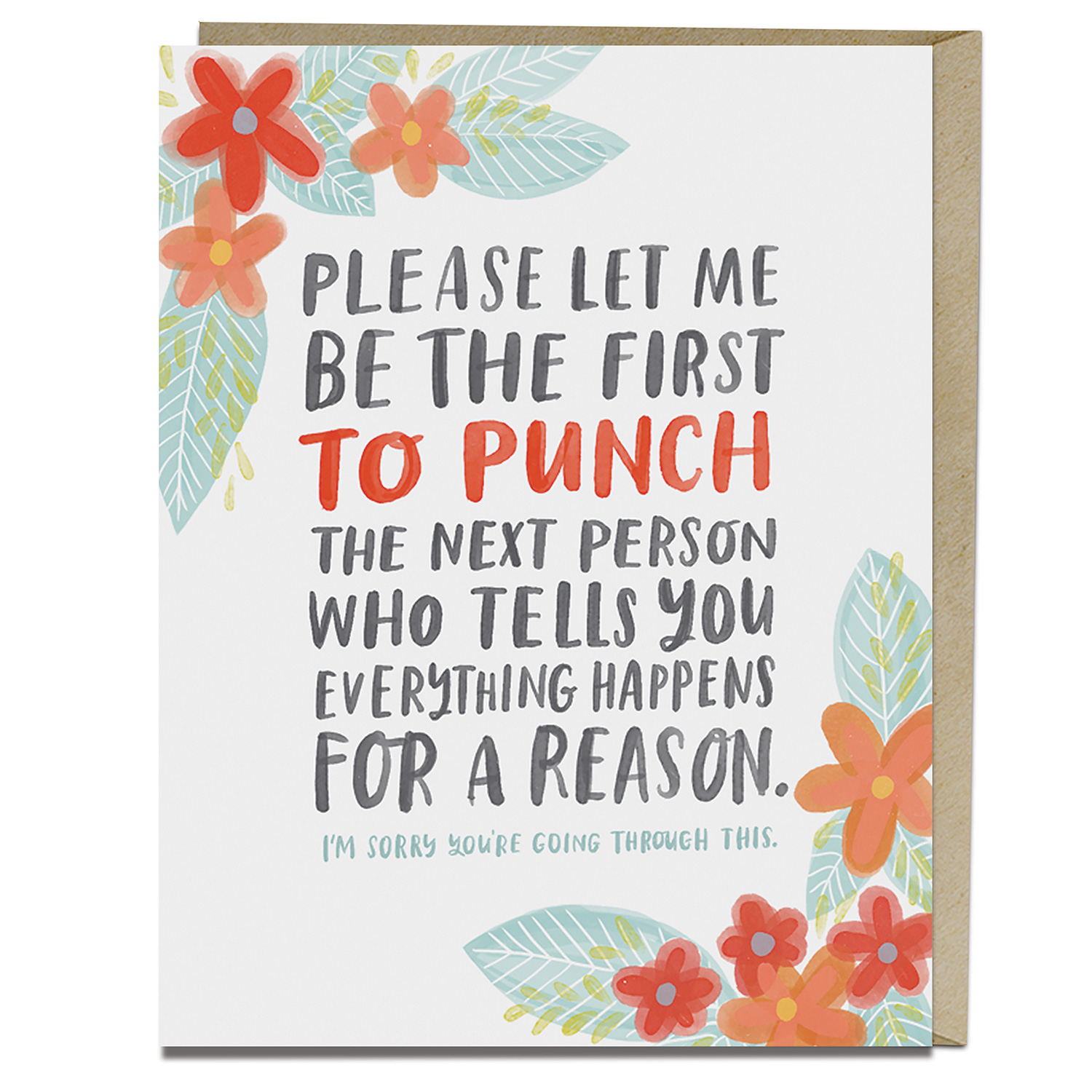

As part of our campaign with FVCK CANCER—a kickass head coverings brand working to support those struggling with hair loss due to chemotherapy—we reached out to designer Emily McDowell. Emily was diagnosed with Stage 3 Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 2001 when she was only 24. During the next 9 months of treatment, she watched as family and friends wrestled with finding the right words to say. And the sympathy cards she received didn’t help—ranging from cheesy to cold, nothing spoke to the situation she was in. This spurred her to create her own cliché-free, punchy designs. From finding the humor in nausea to ballsy sarcasm, Emily’s cards say it how it is, while being compassionate and comforting. Check ‘em out below, along with a few of her tips on what to say to someone who has cancer.

Tips for Supporting a Friend with Cancer

Whatever you do, don’t do nothing.

Our culture doesn’t teach us how to talk about illness, so when it happens to someone in our lives, most of us feel really ill-equipped to deal with it. We’re afraid of saying the wrong thing, so we hesitate, and then time passes, and then we feel even more awkward, but now, we also feel guilty, which makes it even harder to reach out. But for the person with cancer, it feels incredibly lonely and painful when friends go silent. Remember that nobody ever died of awkwardness, and if you don’t know what to say, it’s perfectly fine to say that. Your friend doesn’t know how to have cancer, either – and the thing they need most is your offer to simply be there.

It’s not your job to solve it.

Being solution-oriented serves us well in everyday life, so when someone we care about is ill, our first instinct is often to spring into “make-it-better” mode, where we immediately try to help solve their problem with our suggestions, questions, and ideas. But it’s impossible to fix someone’s illness, and you don’t need to.

The most supportive thing you can do for them is to be willing to show up, stay present, listen, and be okay with silence if they don’t feel like talking. Silence isn’t inherently awkward, it just feels that way because we’re not used to it. Fortunately, learning to listen is also a lot easier than coming up with the elusive “right words” that will never come.

What do you say when your main role is to listen?

Find out how they’re feeling. “How are you?” sounds so basic, but most people will appreciate it. It tells the person that you remember and care about what’s happening, but it doesn’t require a long commitment to a conversation if they don’t feel like talking.

Sometimes, a better question is “how are you today?”Adding “today” to your question acknowledges that overall, you’re aware that her life kind of sucks in general at the moment, and that you understand there are good days and bad days. It also takes what can feel like an overwhelming question, like “how am I doing with this whole cancer thing?” and turns it into a manageable one.

Or an alternative: “What’s that like for you?” or “How’s that going for you?”Say you ask your friend how they’re doing, and they say, “Okay. I’m halfway through my radiation.” Instead of offering up your own conclusion or story in response — like, “Wow, halfway done!” or “My aunt really struggled with her radiation,” — this would be a great time to ask, “how’s that going for you?” This gives your friend a lot of latitude to respond however they like, and shows them that you’re interested in hearing about their experience.

What should you never say?

Your friend with cancer doesn’t need or want you to send them links about the healing properties of green juice, or an experimental treatment you read about. Trust that as the person going through this, they’ve spent more time thinking about their treatment options than you could ever spend on their behalf, and they’ve chosen what they feel is the best course of action. If they specifically ask for your opinion, feel free to give it, but never offer unsolicited advice.

Don’t try to come up with a mind-blowing spiritual insight that will give them a new perspective on life, or that will “help them feel better.” For example, you might personally believe that everything happens for a reason, but attempting to impose this belief on someone who’s been diagnosed with an illness will result in them feeling unheard and alienated, which is the opposite of your intention.

Trying to “relate” by bringing up something that happened to you, or a story you’ve heard, can get in the way of the opportunity for you to learn how the person is actually feeling about what they’re going through. And unbridled optimism (“you got this!”) can feel like an empty platitude, with the person ending up feeling like you don’t actually want to hear them.

Small gestures make a big difference.

When you’re feeling like you want to help, you might instinctively want to do a host of things to make the situation better, which can lead to overwhelm or a sense of obligation, which make you less likely to actually help. It’s also a natural impulse to ask the person who’s ill what they need. But doing this requires your friend to do the emotional labor of figuring out what they need (because often, when we’re struggling, we don’t know what we need), and then asking for it, which is hard for anyone who’s already feeling like a burden.

Instead, figure out the one thing that you can do well and with joy, and offer it – or, just do it. Don’t worry if the gesture is too small to feel significant to you; the offer of something small is far better than the alternative of turning away and doing nothing because you feel overwhelmed. And gestures that feel small to us often feel very meaningful to the recipient. The most important thing is to offer something you genuinely feel delighted to do – and then do it.

Emily McDowell is the founder and creative director of Em & Friends. Check out Em & Friends’ full selection of Empathy Cards and supportive gifts at emandfriends.com.

Emily is also the co-author (with Dr. Kelsey Crowe) and the illustrator of the book, “There Is No Good Card for This: What to Say and Do When Life Is Scary, Awful, and Unfair to People You Love.” Find the book here. Cancer collection: https://emandfriends.com/collections/cancer